Rule 3 / Case 2

- Moulton Avery

- Oct 30, 2021

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 4

Field Test Your Gear

Hamilton Wood, February 28th, 2009 Isles of Shoals, Atlantic Ocean, 6 Miles East of ME / NH Coast

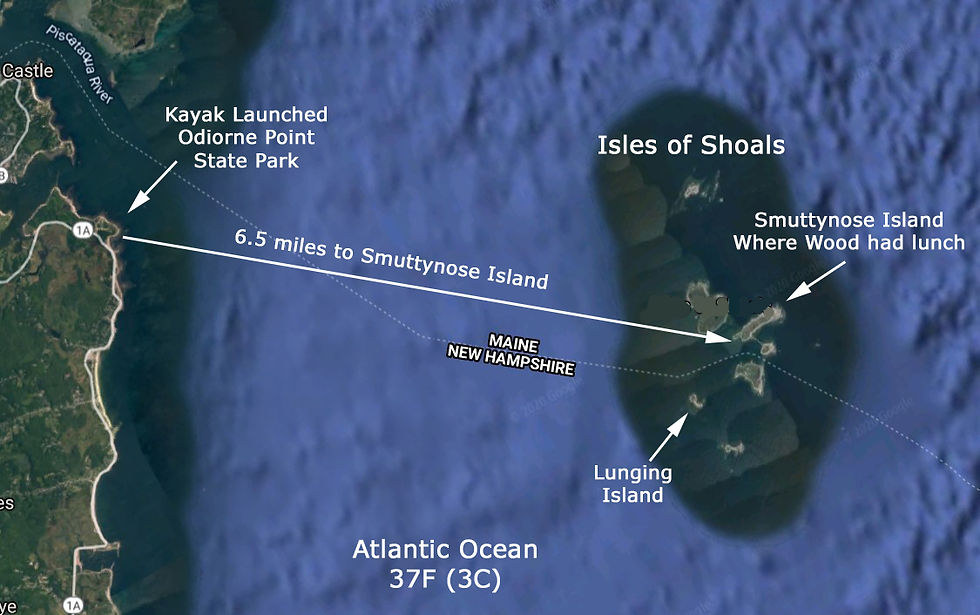

Hamilton Wood, 59, launched his kayak from New Hampshire's Odiorne Point State Park around noon on Saturday, February 28th. His destination was the Isles of Shoals, nine rocky isles located in the Atlantic Ocean, roughly six miles off the New Hampshire/ Maine coast. He was paddling alone (solo), wearing a wetsuit of unknown thickness, and a PFD. The water temperature was 37F (3C).

(Click to expand images)

Shortly after he launched, a concerned citizen in the Odiorne Point area called Coast Guard Station Portsmouth Harbor (Located 1.75 miles north of the park) and reported a kayaker in what appeared to be rough seas. The Coast Guard investigated, found his car, learned both who he was and his intended route, and launched a 47-foot motor lifeboat that followed the same route.

The Coast Guard boat located Wood around 1:30 pm approximately 6 miles offshore (his average paddling speed was a respectable 4 knots), spoke with him, and determined that he wasn't in trouble. Wood told them he was planning on having lunch on nearby Smuttynose Island.

He agreed to call the Coast Guard on his cell phone before leaving the island, and again when he reached his car and was off the water. Wood called at 3 pm to say he was heading back. "At that point, we re-emphasized to him to contact us when he arrived because the seas were getting a bit heavier," said Coast Guard Petty Officer Matthew Merical.

That was the last time anyone heard from him. Based on his previous crossing speed, he should have arrived back at Odiorne Point around 4:30 pm. When he failed to check in by 5pm, the Coast Guard went back to the state park and checked his car again. "Once it was determined the vehicle was still there and we couldn't contact him via cell phone, we launched the 47-foot boat again", said Merical.

The Search for Wood

That was the beginning of a huge search effort that included the 47-foot motor lifeboat, the cutter Reliance, and a Coast Guard helicopter and plane. In addition to Maine and New Hampshire marine patrols, police and fire units from Kennebunk, Ogunquit, York, Kittery, New Castle and Rye also responded.

A big problem immediately encountered by the searchers was lack of light. Sunset on 2-28-12 was at 5:30pm and Nautical Twilight was at 6:32pm. Even if searchers had been able to arrive on scene immediately, they would have had no more than 60 minutes of gradually diminishing twilight in which to locate Wood before darkness fell.

According to Coast Guard Chief John Roberts, conditions were bad Friday night. Very poor visibility, combined with 8ft - 10ft swells, forced most searchers to return to port.

The search resumed at daybreak, and Wood's kayak was found capsized and floating in the ocean near Boon Island, which is 11 miles NE of Smuttynose and nowhere near his intended route.

His paddle, with a float attached, was recovered with the kayak. This indicated that he had attempted to self-rescue.

Video of the Kayak Recovery

The search for Wood continued until it was finally called off on Sunday, having lasted 40 hours and covered 400 square miles of ocean. In addition to the 37F (3C) water temperature, a snowstorm that dropped a foot of snow Sunday evening was a contributing factor in the Coast Guard's decision to suspend the search. In reality, there's no way that Wood could have survived even the first night in the water.

Wood's body was recovered by the Coast Guard two months later, washed up on the rocky shore of Lunging Island, which is on the New Hampshire side of the Isles of Shoals, and only ¾ of a mile (1.2 km) from Smuttynose Island, where he had eaten lunch. (Click to expand images)

This indicates that Wood very likely capsized in the rougher water between Smuttynose, Star, and Lunging Islands shortly after leaving on the return leg of his trip. When his self-rescue failed, he was either unable to swim to shore or unable reach a spot on the rocky shoreline where he could get out of the water.

In the aftermath of this tragedy, family and friends described Hamilton Wood as a dedicated father to his two teenage sons, a gifted educator, and active outdoorsman. His wife, Lisa Wood told the press that he was a victim of bad luck, not recklessness, saying that he was "an extremely experienced kayaker". His brother-in-law, David Eberhart, was quoted as saying "He has done this trip out to the Isles numerous times. He's very conscientious about watching the weather and making sure conditions are OK for doing this."

Lessons Learned Several things are obvious from the circumstances surrounding the incident:

He was paddling solo.

The water temperature was 37F (3C).

The weather and sea state were worse on the return leg of the trip.

He capsized, failed to roll & had to wet-exit.

His paddle-float self-rescue failed.

He was unable to contact the Coast Guard while in the water.

He was unable to swim to shore, or if he reached shore, unable to climb out of the water.

The Search and Rescue operation began after sunset.

He had no strobe light or other way of alerting rescuers to his position after dark, or was too incapacitated by cold to use them.

Even if conditions had been flat calm, finding him in the dark without a light source was highly unlikely.

His wetsuit would not have kept him alive overnight.

Field Testing Proper field-testing of his gear, including solo rescue practice below 40F (4.4C), with a paddle float - in rough-water - would have clearly demonstrated to Wood that both his thermal protection and his self-rescue skills were inadequate for the water temperature and the conditions in which he chose to paddle. Complacency For most people, making a trip multiple times without encountering any problems doesn't sharpen the senses. More often than not, it breeds a certain complacency that can lead to overconfidence - a major contributing factor in outdoor recreation accidents. This was no ordinary outing. It was a solo, very exposed, 6 mile open-ocean crossing - on brutally cold water - in winter.

Underestimating the Risk

Regardless of a paddler's level of experience, 37F (3C) water isn't just a little more dangerous than, for example, 50F (10C) water. It's many orders of magnitude more dangerous. If the paddler is solo, as Wood was, the risk simply cannot be overstated. As many incidents have demonstrated over the years, those are circumstances in which even a small miscalculation like missing a brace and failing to self-rescue can get you killed.

A Remote and Exposed Location

Isles of Shoals has the potential for being a very dangerous place for small, human-powered craft like sea kayaks. In fact, a place name like Isles of Shoals should send a strong cautionary message to any paddler. A shoal is a shallow area surrounded by deeper water. Shoals, sandbars, and underwater ledges often cause waves to steepen and break – even when the water appears relatively calm. Because of its location far offshore, Isles of Shoals has very little shelter from the wind or waves.

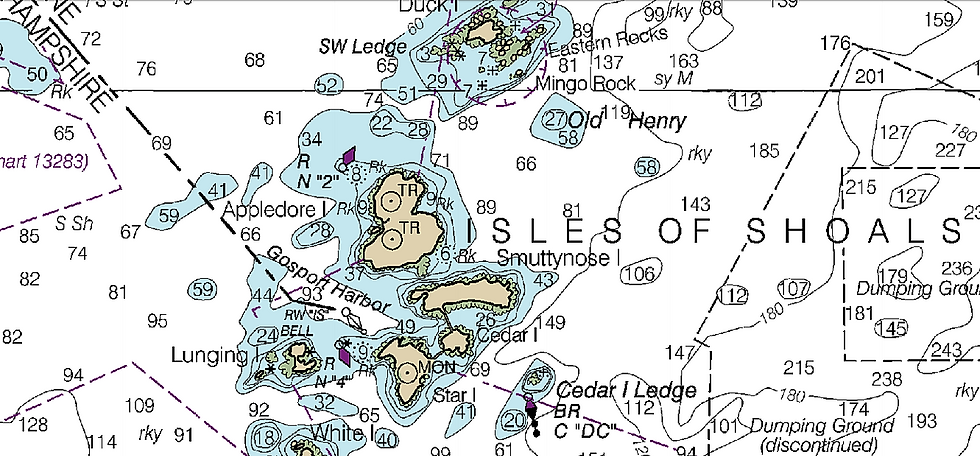

As indicated on the Nautical Chart below, many large shoals and rocks surround the islands. Most of the islands have very rugged shorelines and many have very steep sections or cliffs. As conditions get worse, waves in an area like this can quickly change from relatively tame to extremely rough, and safe landing spots can become very limited.

Very Complex Wave Patterns

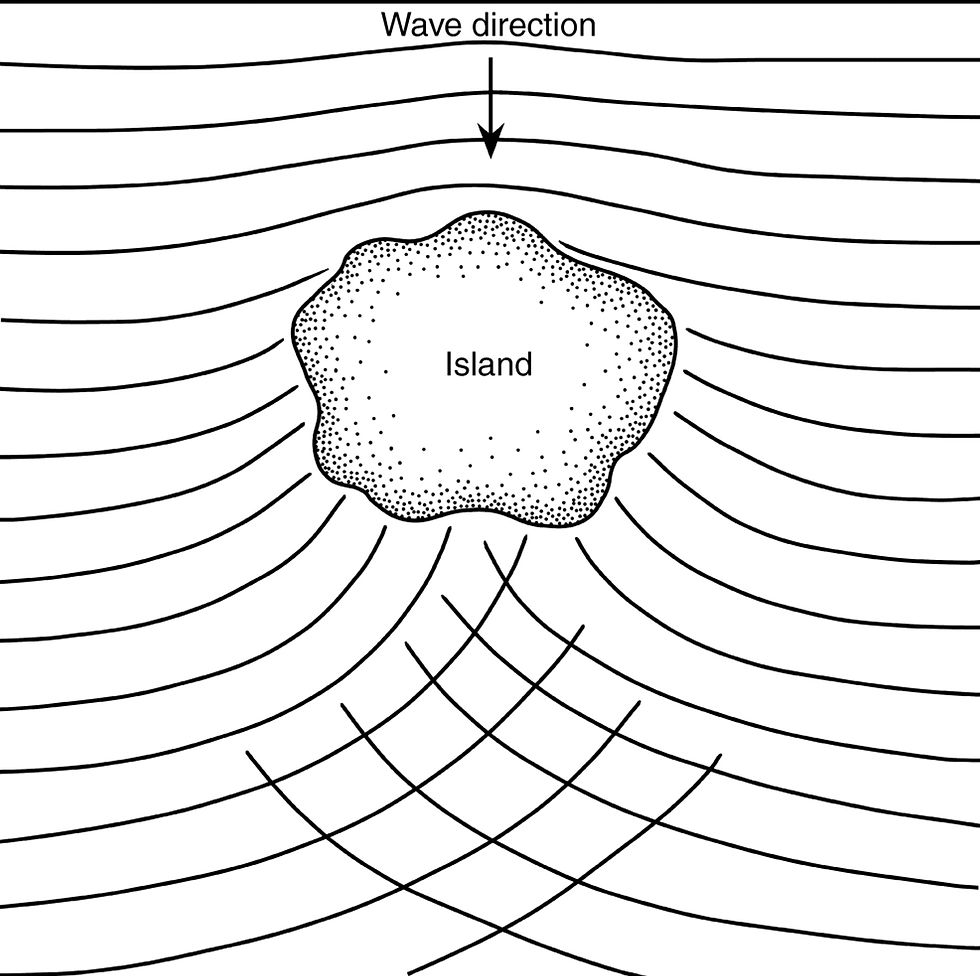

Islands form an obstacle to waves, causing them to “bend” or refract. The figure below illustrates what happens when waves encounter an island. They wrap around it and converge from opposite directions on the down-wave side. These intersecting wave patterns can create very rough and confused conditions. When this happens in an area with a lot of islands and underwater ledges, the seas can become large and complex enough to easily overwhelm small craft.

Take another look at the picture of White Island Lighthouse at the top of this page. It's not just the size of the ocean waves that creates the extremely rough conditions around the island - it's the waves interacting with the island - and with each other - that increases their size and complexity. When waves interact with each other, the results can be really dramatic.

This excellent 2-minute video, shot in slow motion on the coast of Oregon, shows how intersecting waves can amplify each other and create really fierce conditions.

Here's another example of wave reflection and underwater ledges creating extreme conditions at Depoe Bay on the Oregon Coast in December 2021. In this case, the ocean swell was 17 feet compared to 8 - 10 feet for Isle of Shoals when Wood capsized. However, the dynamics are the same, and in terms of bathymetry, Isle of Shoals is a more complex area than Depoe Bay.

A Capsize Can Be Fatal

At a certain point, which varies according to the skill of the paddler, conditions become so difficult that a capsize is almost guaranteed. In such conditions, self-rescue using a paddle float is extremely unlikely to succeed, and failure to recover, either by rolling or self-rescue, is often fatal.

Wood's body was recovered on Lunging Island, .75 miles from where he started paddling back to Odiorne Point State Park. The island has only one small beach where it would be easy to get out of the water in rough conditions. Smuttynose Island, his departure point isn't much better.

Although Wood had made this trip many times before, it's very unlikely that he'd been in the area when the seas started getting as big as they were on the day he died. It appears that he was within half a mile of all three islands when he capsized, but Isles of Shoals is a particularly bad place to capsize because there are so few places where it's easy to get ashore and out of the water - particularly in rough conditions.

Major Contributing Factors

Not Dressed For Water Temperature (Underdressed)

Unable To Recover From Capsize

Unable to Call For Help (Unable to use cell phone in the water)

Being Complacent / Overconfident

Lack of Weather Awareness

Unable To Deal With Wind and Waves

No Light - Invisible At Night

Paddling Solo

Commentaires